Ahmed Elsheaita1, Nesrin Said Tolba1

1 Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, Egypt

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Ahmed Elsheaita

Consultant Hepatologist,

Assistant Professor of Hepatology, Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Endoscopy Unit,

Department of Internal Medicine, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University,

Clinical Fellow of Advanced Hepatology, University of Toronto

Email: ahmed.elsheaita@uhn.ca

ABSTRACT:

Background: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is well known to be associated with mixed cryoglobulinemia, specifically type III, as well as other lymphoproliferative disorders such as B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Castleman Disease (CD) is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder that causes enlarged lymph nodes that can be unicentric or multicentric and might have a similar pattern clinically and pathologically to a rare subtype of mantle cell lymphoma.

Case presentation: We report a case of a 45-year-old male patient presented to our hospital with anasarca, nephrotic range proteinuria, and rapidly progressive renal failure with generalized lymphadenopathy that turned out to be a complex situation of HCV, mixed cryoglobulinemia and mantle cell lymphoma in a background of CD.

Conclusion: HCV is known to have extrahepatic manifestations, in this case it triggered nephrotic syndrome and generalized lymphadenopathy through triggering cryoglobulinemia with mantle cell lymphoma in background of Castleman disease or alternatively, it induced a rare subtype of mantle cell lymphoma that mimics multicentric Castleman disease.

INTRODUCTION:

It has long been proposed that hepatitis C virus (HCV) has a strong association with benign forms of lymphoproliferative disorders, namely mixed cryoglobulinemia1. The pathogenesis, though not well defined, is proposed to be mainly due to chronic antigenic stimulation by chronic HCV infection2. It appears that HCV also has a link with non-benign lymphoproliferative disorders, namely B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, even in the absence of cryoglobulinemia1,2. Though the epidemiological association between HCV and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma is evident, the exact mechanism of oncogenesis is still not clear but chronic stimulation of B-cell receptors is highly suggested3,4. The most common subtype of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma associated with HCV is marginal cell lymphoma which usually develops on background of mixed cryoglobulinemia4 while HCV association with mantle cell lymphoma is relatively uncommon5.

Castleman Disease (CD) is a rare lymphoproliferative disorder that was initially reported by Castleman in 1956. It has been classified into two main types; unilateral CD (UCD) which involves only one region of lymph nodes with mild inflammatory manifestations. This type of CD is usually treated by surgical excision of the affected lymph node(s). The second type of CD, which is usually more aggressive, is the multicentric CD (MCD), which is characterized by affection of many lymph node regions with severe inflammatory manifestations6, elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) and high C-reactive protein (CRP)7.

Histologically, CD has also two main types; the hyaline vascular (HV) type which usually corresponds to UCD and the plasma cell (PC) type which usually presents as MCD8. However, in some instances the features of both histological types may be present being called mixed type which might presents as UCD or MCD9,10.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an aggressive B-cell lymphoma which accounts for around 3-10% of all lymphomas and characterized by a pathognomonic chromosomal translocation; t(11;14) which leads to overexpression of Cyclin D1 that has a major role in cell cycle control8,11. In this case report, we report a diagnostic dilemma of a possible triple association between HCV, CD and MCL on one side and the diagnosis of a rare subtype of MCL which presents clinically and pathologically in a similar pattern to MCD on the other side.

CASE PRESENTATION:

A 45-year-old male farmer from rural origin nearby Alexandria, Egypt presented to General Medicine Outpatient Clinic, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University, complaining of a gradual onset progressive lower limb edema, abdominal distension, lethargy and general fatigue. His initial laboratory investigations showed hypoalbuminemia, positive HCV antibodies (HCV Ab) using third generation enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) with normal liver enzymes and mildly increased blood urea (20 mmol/L) while serum creatinine was within the normal range (97.26 µmol/L). On general examination the patient was in mild distress, vital signs within normal limits apart from low grade tachypnea and low-grade fever. There was cervical and axillary firm lymphadenopathy bilaterally with no tenderness, hotness or redness. Chest showed decreased equal air entry bilaterally, moderate abdominal distension and lower limb edema.

Abdominal ultrasonography was done upon admission that showed normal sized liver with diffuse homogenous echo pattern with fine accentuated periportal fibrosis and no cirrhotic changes, moderately enlarged spleen (17 cm) with few hypoechoic focal parenchymal lesions at the upper and lower poles ranging from 7 mm to 5 cm in diameter with enlarged splenic lymph nodes (4 cm), both kidneys were relatively enlarged in size (around 12.5 cm in longitudinal length) and showing increased parenchymal echogenicity with prominent medullary pyramids and accentuated corticomedullary differentiation suggestive of medical nephropathy. Moderate ascites and features of bilateral pleural effusion were also observed. Laboratory investigations (during admission) – summarized in Table 1 – showed progressive impairment of renal function (serum creatinine 185.68 µmol/L) which deteriorated dramatically in the following few days (serum creatinine 548.2 µmol/L). It showed also high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (397 U/L) and complete blood count showed normocytic normochromic anemia, leukocytosis with absolute lymphocytosis with small mature lymphocytes with clumped chromatin and smudge cells. Sepsis workup that consisted mainly of a chest x-ray, complete urine analysis and blood culture didn’t show any source of infection. Twenty-four-hour protein in urine showed nephrotic range proteinuria (5.4 g/day) with consumed complement 4 (C4) (0.08 g/L) and lower normal range of complement 3 (C3) (0.98 g/L). There was elevated β2 microglobulin, LDH and C-reactive protein (CRP) as well as positive rheumatoid factor (RF) and cryoglobulin. HCV Ab was positive with HCV-RNA PCR showing moderate viremia (443000 IU/ml), otherwise hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies were both negative, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) IgM also both were negative.

TABLE 1 – Summary of laboratory investigations upon admission:

| Investigation | Results | Reference |

| Serum Creatinine | 185.68 µmol/L | 35.37-114.95 |

| Blood urea | 43.57 mmol/L | 7.14-14.28 |

| AST (SGOT) | 33 U/L | Up to 35 |

| ALT (SGPT) | 17 U/L | Up to 40 |

| Serum Alkaline phosphatase | 96 U/L | Up to 120 |

| Serum bilirubin (Total) | 3.42 µmol/L | Up to 17.1 |

| Serum albumin | 23 g/L | 35-50 |

| Serum Uric acid | 517.48 µmol/L | 208.18 – 428.26 |

| Random blood sugar | 5.2 mmol/L | <5.6 |

| HCV Ab – ELISA 3rd generation | Positive | Negative |

| HbsAg | Negative | Negative |

| HCV RNA PCR Quantitative | 443000 IU/ml | Low Positive: <10000 Moderate Positive: 10000-80000 High Positive: >80000 |

| HIV Ab | Negative | Negative |

| CMV IgG Ab | Positive | Negative |

| CMV IgM Ab | Negative | Negative |

| EBV IgG Ab | Positive | Negative |

| EBV IgM Ab | Negative | Negative |

| β2 Microglobulin | 6.1 mg/L | 0.8-1.8 |

| LDH | 397 U/L | Up to 250 |

| Complement 3 (C3) | 97.9 mg/dl | 90-180 |

| Complement 4 (C4) | 8.4 mg/dl | 10-40 |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 23 mg/L | 0-10 |

| Cryoglobulin | Positive | Negative |

| 24-hour protein in urine | 5400.5 mg/day | Up to 150 |

| Hemoglobin | 9.4 g/dL | 13-15 |

| Platelet count | 211 103/µL | 150-450 |

| White blood cell count | 30.7 103/µL | 4-10 |

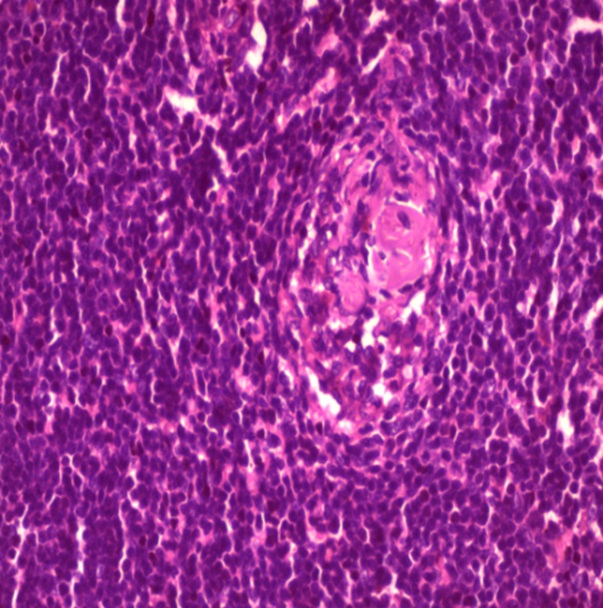

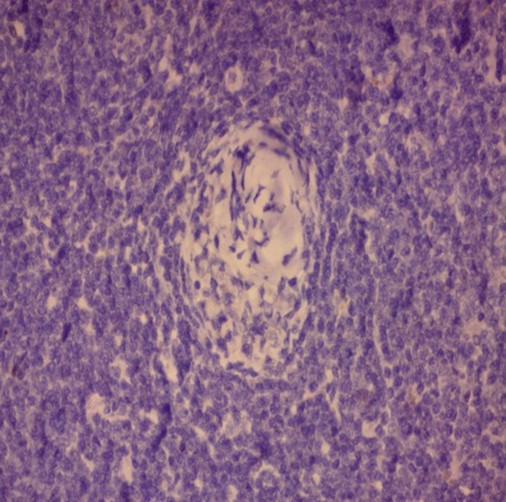

Ultrasonography of neck and axilla showed few bilateral cervical lymph nodes measuring up to 1.4 cm X 1 cm and bilateral axillary lymph nodes reaching up to 5 cm X 2.5 cm. An excisional biopsy was done from a surgically accessible right axillary lymph node. Microscopic examination of the excisional biopsy revealed monotonous population of lymphocytes with irregular nuclei, scattered large cells with vesicular nuclei, the lymphocytes are seen surrounding blood vessels which are surrounded by hyalinized onionskin-like collagenous material suggestive of MCL in background of mixed type CD (plasma cell type and hyaline vascular type) (Figure 1).

A

B

C

Figure 1: Histopathology of the excisional biopsy

(A-B) H&E showing CD merging into MCL (x 10)

(C) H&E showing the onion skin appearance (x40)

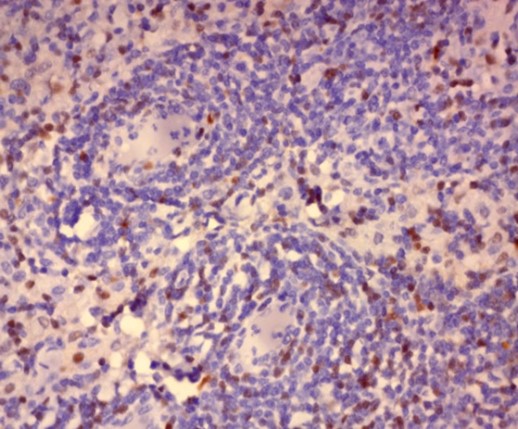

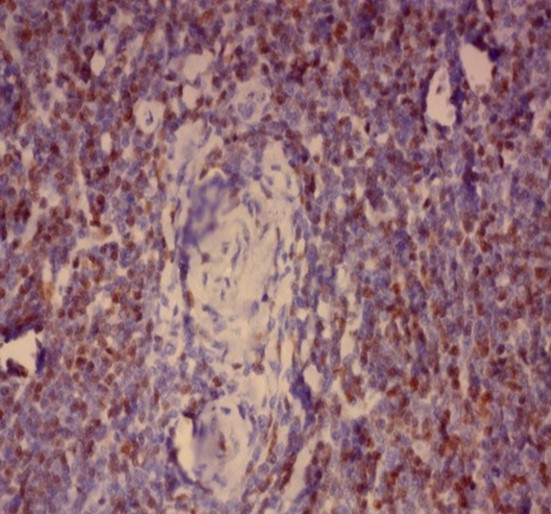

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue blocks of the excised lymph node biopsy for HHV-8, Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP-1), CD 138 and Cyclin D1. The cells stained negative for HHV-8 and LMP-1 antigen while diffuse nuclear positivity was noted for Cyclin D1 as well as scattered cytoplasmic positivity for CD138 denoting the presence of plasma cells (Figure 2).

A

D

B

E

C

F

Figure 2: Immunohistochemistry showing

(A-B) Negative nuclear staining of HHV-8 and negative membranous and cytoplasmic staining of LMP-1 respectively. (x40)

(C) Scattered positive cytoplasmic staining of CD138 in scattered plasma cells surrounding thick walled hyalinized blood vessels. (x40)

(D-F) Diffuse positive nuclear staining of Cyclin D1 starting from around the thick-walled walled vessels merging into the diffuse lymphomatous population. (x40)

Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry showed that the cells are CD 5/19, CD 22, CD 37, FMC7 positive, lambda light chains was strong positive, CD 2, 10, 23 negative and Kappa light chains negative, features suggestive of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (score 1/5) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Flowcytometry showing positive Lambda light chains, CD 5/19, CD 22, CD 37 and FMC7 with negative Kappa light chains and CD 23.

The patient was referred to oncology clinic for a plan of management; according to our local protocols the patient should receive Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin (Vincristine), Prednisone (CHOP) regimen, but the decision was made to postpone CHOP till improvement of renal functions and to begin pulse corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 500 mg daily for 3 days) followed by maintenance oral corticosteroids together with diuresis, broad spectrum antibiotics and general supportive measures with close follow up of renal functions and blood count in a trial to improve renal status before initiation of the first cycle of chemotherapy.

The patient responded dramatically in few days; edema decreased in a significant way and renal functions improved (serum creatinine improved to 221.05 µmol/L). The team decided to initiate the first cycle of CHOP as the benefits outweighed the possible risks. A few days later the patient suffered from severe gastritis, nausea, vomiting and low-grade fever together with severe psychological distress and refusal to take medications and he asked to leave the hospital against medical advice. After a few days he died at home after further deterioration in his level of consciousness.

DISCUSSION:

In this case, the simultaneous occurrence of nephrotic range proteinuria (due to cryoglobulinemia) along with generalized lymphadenopathy and systemic manifestations raised the suspicion of an alternative diagnosis. In addition, the appearance of MCL in background of CD pointed to the necessity of more investigations.

The etiology and pathogenesis of CD is unknown; however many viruses are incriminated in the pathogenesis, mainly chronic HHV-8 and HIV12 and to lesser extent EBV13. Fewer case reports showed association with HCV7.

Several studies recognized the importance of considering CD, particularly MCD, as a diagnosis in any case of lymphadenopathy with constitutional manifestations even with negative HHV-8, which led to a new entity called idiopathic MCD (iMCD) with specific diagnostic criteria6, especially that B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (a known complication of cryoglobulinemia) usually doesn’t present with constitutional manifestations, elevated CRP and/or hypoalbuminemia8.

Aside from persistently normal platelet count, the rest of clinical and laboratory findings matched with Thrombocytopenia, Anasarca, Fever, Reticulin myelofibrosis and Organomegaly (TAFRO) syndrome, especially that TAFRO is considered as a variant of iMCD14, and though thrombocytopenia is one of the major diagnostic criteria for TAFRO syndrome15, flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry are critical to confirm the diagnosis.

Flow cytometry and positive Cyclin D1 staining excluded TAFRO syndrome and confirmed the diagnosis of MCL, however other clinical and laboratory findings matching with TAFRO and iMCD were confusing, in a picture that could be in keep with overlap between both diseases. In literature, there were very few reports reporting a variety of MCL sharing clinical and pathological features of CD mainly the plasma cell type8 and even more rarely the hyaline vascular type16, in both cases and to the best of our knowledge none reported its association with HCV.

Management here was challenging. The decision of initial treatment with pulse corticosteroids, as the treatment strategy proposed by the All-Japan TAFRO Syndrome Research Group14, made an initial dramatic clinical response. However, initiating CHOP thereafter didn’t result in clinical improvement. Though recent evidence shows that Rituximab-CHOP regimen seems to be a good option for treatment for both MCL17 and iMCD separately, this regimen effect was not studied in association with HCV7.

CONCLUSION:

While HCV is known to be a culprit of cryoglobulinemia and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, sometimes it can cause rare pathological mimics which needs special consideration to design the optimum management plan. In our case, pathology investigations pointed to a rare variant of MCL, this point to the importance of immunohistochemistry and flowcytometry in any case of B-cell lymphoma with atypical manifestations. Further research is warranted to investigate the pathophysiology and management of this rare variant and its potential association with HCV and CD.

Conflict of Interests

AE is the Editor-in-Chief at the Middle Eastern Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, http://www.mejmms.org

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Asmaa Nasr, Clinical Pathology resident, Alexandria University Hospitals, for her help in examining and producing the flowcytometry charts. Written informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report.

REFERENCES:

- Luppi M, Torelli G. The new lymphotropic herpesviruses (HHV-6, HHV-7, HHV-8) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in human lymphoproliferative diseases: an overview. Haematologica. 1996;81(3):265-81.

- Martyak LA, Yeganeh M, Saab S. Hepatitis C and Lymphoproliferative Disorders: From Mixed cryoglobulinemia to Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;7(8):900-5.

- Vannata B, Zucca E. Hepatitis C virus-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. ASH Education Program Book. 2014;2014(1):590-8.

- Armand M, Besson C, Hermine O, Davi F. Hepatitis C virus – Associated marginal zone lymphoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2017;30(1-2):41-9.

- Lin RJ, Moskovits T, Diefenbach CS, Hymes KB. Development of highly aggressive mantle cell lymphoma after sofosbuvir treatment of hepatitis C. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e402.

- Fajgenbaum DC, Uldrick TS, Bagg A, Frank D, Wu D, Srkalovic G, et al. International, evidence-based consensus diagnostic criteria for HHV-8–negative/idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2017;129(12):1646.

- Talukder DY, Delpachitra SN. Multicentric Castleman’s Disease in a Hepatitis C-Positive Intravenous Drug User: A Case Report. Case Reports in Medicine. 2011;2011.

- Igawa T, Omote R, Sato H, Taniguchi K, Miyatani K, Yoshino T, et al. A possible new morphological variant of mantle cell lymphoma with plasma-cell type Castleman disease-like features. Pathology – Research and Practice. 2017;213(11):1378-83.

- Liu J, Han S, Ding J, Wu K, Miao J, Fan D. COX2-related multicentric mixed-type Castleman’s disease in a young man. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2005;2(7):370-5.

- Nagubandi R, Wang Y, Dutcher JP, Rao PM. Classic Case of Unicentric Mixed-Type Castleman’s Disease. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(36):e452-e5.

- Fichtner M, Dreyling M, Binder M, Trepel M. The role of B cell antigen receptors in mantle cell lymphoma. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2017;10(1):164.

- Carbone A, De Paoli P, Gloghini A, Vaccher E. KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman disease: A tangle of different entities requiring multitarget treatment strategies. International Journal of Cancer. 2015;137(2):251-61.

- Chen CH, Liu HC, Hung TT, Liu TP. Possible roles of Epstein-Barr virus in Castleman disease. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:31.

- Hou T, Dhillon J, Xiao W, Jaffe ES, Sands AM, Neppalli V, et al. TAFRO syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Human Pathology: Case Reports. 2017;10(Supplement C):1-4.

- Masaki Y, Kawabata H, Takai K, Kojima M, Tsukamoto N, Ishigaki Y, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria, disease severity classification and treatment strategy for TAFRO syndrome, 2015 version. Int J Hematol. 2016;103(6):686-92.

- Siddiqi IN, Brynes RK, Wang E. B-Cell Lymphoma With Hyaline Vascular Castleman Disease–Like FeaturesA Clinicopathologic Study. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2011;135(6):901-14.

- Doorduijn JK, Kluin-Nelemans HC. Management of mantle cell lymphoma in the elderly patient. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1229-36.

For citation:

Elsheaita A., Tolba N., (2024), HCV Associated Mixed Cryoglobulinemia and Mantle Cell Lymphoma in Background of Castleman Disease: a case report. MEJMMS, 1(1), 1004-12; mejmms.org/2024/08/12/hcv-associated-mixed-cryoglobulinemia-and-mantle-cell-lymphoma-in-background-of-castleman-disease-a-case-report/

Leave a comment